*I wrote this essay over the last few weeks for a 300-level English course– It’s an example of the scholarly work in the noir genre I hope to do when I begin post-graduate studies. Enjoy.

Cover designed by Megan Wilson

“You won’t need much of anybody’s help. You’re good. You’re very good. It’s chiefly your eyes, I think, and that throb you get in your voice when you say things like ‘Be generous, Mr. Spade.’”

Sam Spade: Masculinity under Threat

The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett is a definitive piece of the hardboiled noir fiction genre. As such its protagonist, Sam Spade, is the subject of frequent discussion and review, particularly those studies pertaining to modern masculinity. Current scholarship topics tend toward definition, although “noir is notoriously difficult to define,” and speak of the genre and The Maltese Falcon as a “symbolic stage upon which crisis is negotiated via changes in gender paradigms” (Entin 86; Dietze 645). As a result, the book’s sexual dynamics and threatening femme fatale are the central topics of most Spade-centric discourse. Brigid O’Shaughnessy, the veiled villainess, wages a manipulative battle with Sam, each hungry to serve their own ends at the expense of the other. Ultimately, Sam Spade is the victor, but the cost outweighs the benefit of such an outcome. The ‘hero’ is reduced to despicable ends in his quest to define and defend his masculinity throughout the novel, demeaning each female character with oppressive, sexist behaviors. He relies on ‘illusions of order’ and ‘intellectual control’ to defend his masculinity from the onset of ambitious women, and becomes an archetypal example of the fearful white male chauvinist in modern society.

Hammett’s 1930 magnum opus is burgeoning with gender friction and social commentary. By connecting Sam Spade’s fear of emasculation with his detective fueled ‘will-to-know’, we find a man plagued with insecurity. As Sam’s masculinity comes under threat, he lashes out with his greatest tool, his insight and detection, to menace what he perceives to be encroaching and dangerous females. Thus he exerts his intellectual control over these women to restore his illusions of order, or preserve his masculinity. Regardless of its fame, The Maltese Falcon appears to be free of detailed scholarly analyses that speak to these themes. The authority of Hammett’s words and my inquiry will hopefully solidify these proposed ideas as the essay develops. Additionally, sources are provided severally which prod the margins of this previously untreated issue: The first, that of Sam Spade’s fear of emasculation and his resulting misogynistic backlash, and the second, that of his need to preserve his illusions of order in an increasingly disordered social realm. At the convergence of these two complications, wonderful analytically uncharted territory is apparent.

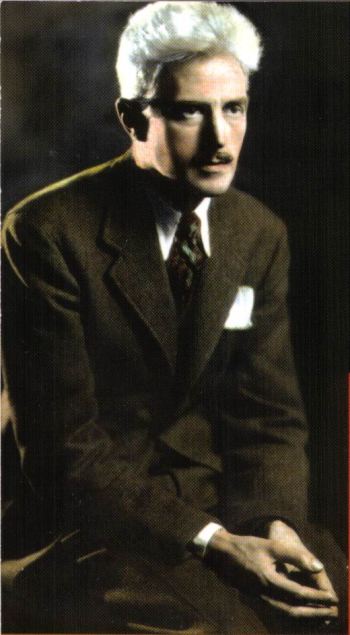

Dashiell Hammett, Author of The Maltese Falcon

Mr. Spade is a hard-edged force of masculinity, an unbending bastion of iron-wrought will, and an estranged loner from society. Sara Paretsky explained his over-the-top persona, saying “because crime fiction focuses so strongly on issues of justice and society, characters have to be exaggerated to make social points” (12). Simply stated, Sam Spade is a social statement. He is “the world weary non-hero, betrayed from within the institution that once nurtured and protected him, who discovers that no prospect pleases, and that all men (and women) are vile” (Winks 8). In addition to his already volatile psyche, Sam’s chauvinism and sexual anxieties create a plethora of gender conflicts within the text. Priscilla Walton tells us that “the originary hardboiled narrative arose in an era fraught with sexual tensions, since the advent of the Great Depression generated a backlash against shifting gender roles” and “in the matter of misogyny, hardboiled detective fiction undergirds the whole system of Western patriarchy” (127). She speaks to the complex social issues of the era in which the book was written, issues that may not appear as widespread contemporarily as they may yet be. Sam Spade is an ideal contender for gender conflict as a misogynistic hallmark of female repression and abuse. Yet he’s believed to be “the genre’s ideological model of male self-containment,” which begs fearful questions about independent men and their role models (Cooper 24). If men since the 1930s have viewed Mr. Spade as a role model, what implications does this portend for society? Especially a society founded on a patriarchal order? If hardboiled detective fiction undergirds the whole system of Western patriarchy, then how vital a foundational strut is Sam Spade?

Accepted gender role paradigms were shifting as this novel was being distributed, and men were fighting insecurity and estrangement in a society that no longer defined their masculinity for them. Modern Masculinity, at its core, had always been defined by strength, self-control, success (especially in the workplace), and individualism. As women’s roles in society began to evolve and change, many men felt displaced. Paretsky pointed to the 19th Amendment as a possible cause for the gender inequality present in The Maltese Falcon when she said, “After widespread agitation for the vote, the image of active women changed. Now they were seen as a species of monster who wanted to strip men of all their rights” (12). She concluded that “[men] believe that when a woman moves into a masculine domain their very masculinity is under attack” (13). Fear of this threat is a defining theme in The Maltese Falcon. Sam Spade is consumed by his fear of emasculation, and it causes him to react in oppressive ways towards perceived female threats.

Yet at his core Sam Spade is a detective, personally and professionally, and defines his masculinity by his success in this arena. As an independent working man, he is completely reliant upon his ability to accurately re-construct means of injustice and crime perpetration through deductive reasoning, logic, and investigation. When his masculinity comes under threat, he uses these same finely tuned methods to preserve and restore his manly dominance. Mr. Spade is constantly striving to obtain and maintain order, or at least the illusion of such; for his masculinity to remain intact, he must successfully ‘solve’ each potential affront to it. In his article, “Lead Birds and Falling Beams,” Dean DeFino explains:

The detective enters the scene of the crime after the fact and, through a feat of analyses, constructs a chain of effects and causes back to the source of the crime – mode and motive – which, while not annulling the deed (the body is still dead), gives the reader a sense of intellectual control over it. The story redeems that sense of order and control by (fictionally) exposing its logic, its cause–and-effect chain, how one thing leads to another (74).

Sam re-orders a crime scene to achieve the same equilibrium that the readers of detective fiction enjoy, the illusion of order or intellectual control. His sense of order is not only dependent upon his success as a detective, but his dominance as a man. When his masculinity or his accepted gender role paradigms are threatened, he reacts by an attempted return to his perceived order. Both forms of order hinge on Sam’s ability to control the object of threat; for crime, as he exposes its means of execution he gains intellectual control over it. With women, as he imposes his will upon them and hedges their advances into his social sphere he restores his emasculated authority. Sam’s already intense reactions are further enhanced when his illusion of order is challenged by secrets or dishonesty. His ‘will-to-know’ entirely consumes him, for his fear of emasculation is inexorably tied to the possibility of a woman besting him intellectually.

Three female characters star opposite Sam in the novel, and each seemed no better than a prop for his advances. All of his interactions with these woman teeter anxiously on the edge of flirtation and raw sexual lust, a balance as dangerous as it is unlikely. He touches their bodies, plays with their hair, coddles them, scolds them, kisses them (yes each of them), and in the case of Miss O’Shaughnessy sleeps with them. Sam keeps these women emotionally distant from his true desires and feelings, even when they express interest. For him, they are simply ‘girls’; too silly or inexperienced to offer him anything worthwhile. When his impenetrable nature is challenged by Brigid, he reacts harshly—perhaps in denial of real feelings too awkward or uncomfortable to confront. Ironically, he dismisses these women as naïve, immature, or flighty when such adjectives more accurately describe himself. Mr. Spade’s relationships with the opposite sex are tainted by his need to defend his perceived masculinity—were he to surrender any level of control, his illusion of order would be compromised.

Humphrey Bogart as Sam Spade, Mary Astor as Brigid O’Shaughnessy, Gladys George as Iva Archer, and Lee Patrick as Effie Perine

Although examples abound, three particular scenes from The Maltese Falcon will be presented and unpacked as indicative of the illusion of order in defense of masculinity argument. Throughout the novel Sam Spade seems to grapple with his misogynistic impulses, which are a common symptom of backlash due to shifting gender paradigms. I would not go so far as to say that he hates women (as misogyny is typically defined), but that he fears and distrusts them so much that it corrupts his interactions with them. His manly impulses drive his lusty sexual attraction for them, while his misogyny simultaneously attempts to protect him from them. Here is the first scene that illustrates my argument, when Brigid O’Shaughnessy pleads with Mr. Spade for help:

“I’ve given you all the money I have.” Tears glistened in her white-ringed eyes. Her voice was hoarse, vibrant. “I’ve thrown myself on your mercy, told you that without your help I’m utterly lost. What else is there?” She suddenly moved close to him on the settee and cried angrily: “Can I buy you with my body?”

Their faces were a few inches apart. Spade took her face between his hands and he kissed her mouth roughly and contemptuously. Then he sat back and said: “I’ll think it over.” His face was hard and furious (Hammett 57).

Aside from being one of the most memorable exchanges in all noir fiction, this scene is grossly sexist. Sam’s face is “hard and furious” because he wants her to buy him with her body, and he hates her for it. His response is perfectly calculated to preserve his illusion of order (which is based on control) and retain his power over her. By telling Brigid that he would “think it over” he keeps her offer available and places himself in the position of deciding when or if it will be accepted. Sam believes that if he were to succumb to her offer initially, he would be fully in her thrall; a failure that would surrender his masculine power to her feminine usurpation. But Sam succeeds in retaining intellectual control over Brigid, and thus preserves his illusion of order (and his masculinity). We can only guess what Sam Spade is thinking as he denies Brigid’s advances, but it clearly seems linked to the fear of losing something other than virtue; my money’s on masculinity and his illusion of order.

The second interaction that illustrates this thematic formula occurs between Sam and his personal secretary Effie Perine (the second of three females in the novel). For contextual purposes, they are discussing Iva Archer (the third), the widow of Sam’s dead partner Miles (whom Sam had been sleeping with up until Miles’ murder). Sam is sitting at his desk resting his head against Effie’s hip, who stands at his side:

“Are you going to marry Iva?” she asked, looking down at his pale brown hair.

“Don’t be silly,” he muttered. The unlit cigarette bobbed up and down with the movement of his lips.

“She doesn’t think it’s silly. Why should she–the way you’ve played around with her?”

He sighed and said: “I wish to Christ I’d never seen her.”

“Maybe you do now.” A trace of spitefulness came into the girl’s voice. “But there was a time.”

“I never know what to do or say to women except that way,” he grumbled, “and then I didn’t like Miles.”

“That’s a lie, Sam,” the girl said. “You know I think she’s a louse, but I’d be a louse too if it would give me a body like hers.”

Spade rubbed his face impatiently against her hip, but said nothing (Hammett 27).

Effie begins by trying to ascertain Sam’s intentions with Iva. She has obviously seen some signs of a serious relationship between them, yet Sam dismisses all of it as “silly.” The reader gets the subtext that Effie herself is interested in Sam (why else would she be asking?), and then it becomes more apparent when she calls Iva a “louse” and says she’s jealous of her figure. Perhaps she believes that if she looked like Iva she could demand Sam’s affection, instead of being firmly caught in the role of confidant. You will note that Sam admits that he doesn’t know how to deal with women except in “that way,” which is the way that plays with their feelings and teeters between flirting and disgust. The more you examine this passage the sadder it becomes, because you can feel the pain that Sam is inflicting on Ms. Perine when he nuzzles his face against her hip. Basically, he is confirming his desire to “play” with her when he wants while remaining un-entangled romantically. She means nothing to him. Once again, Sam has felt his masculinity come under threat; the threat of the widow Iva’s expectations (now that she is untangled from her marriage), and the threat of Effie’s jealousy, and on both counts he has rebuffed them by straddling his barren stretch of intellectually controlling ground. By remaining aloof to the desires of these women, he not only spurns their advances but also denies responsibility for his actions. In this way, his masculine independence is unmolested and his accepted gender paradigms are unaltered. He successfully avoids the emasculation sure to accompany marriage to his partner’s widow or a relationship with his young secretary.

The final (and most important) scene that illustrates the relationship between Sam’s fear of emasculation and his reliance upon intellectual control and illusions of order occurs near the end of the novel. At this point, Sam is led to believe that Brigid has stolen a one hundred dollar bill. He takes her into a bathroom at gunpoint and they share this interaction:

In the bathroom Brigid O’Shaughnessy found words. She put her hands up flat on Spade’s chest and her face up close to his and whispered: “I did not take that bill, Sam.”

“I don’t think you did,” he said, “but I’ve got to know. Take your clothes off.”

“You won’t take my word for it?”

“No. Take your clothes off.”

“I won’t.”

“All right. We’ll go back to the other room and I’ll have them taken off.”

She stepped back with a hand to her mouth. Her eyes were round and horrified. “You would?” she asked through her fingers.

“I will,” he said. “I’ve got to know what happened to that bill and I’m not going to be held up by anybody’s maidenly modesty.”

“Oh, it isn’t that.” She came close to him and put her hands on his chest again. “I’m not ashamed to be naked before you, but–can’t you see?–not like this. Can’t you see that if you make me you’ll–you’ll be killing something?”

He did not raise his voice. “I don’t know anything about that. I’ve got to know what happened to the bill. Take them off” (Hammett 196). (Italics added)

A pulp cover that illustrates the shower search scene

The bathroom search scene is the most degrading and misogynistic in the novel. Hammett does not go into perverse detail, as if Brigid were performing some kind of strip tease, but the cold manner in which Spade deals with her is shocking. Remember that this exchange takes place after they have slept together. Once again we can see that the woman in the scene has misinterpreted Sam’s behavior. She thought that her relationship meant something to him, and he assures her that it does not. Just like the scene with Effie, the more we dwell on what is happening here, the more painful it becomes; for Sam really is “killing something,” he is killing the part of Brigid that loves him, and killing the part of himself that she loved. This ‘murder scene’ hinges upon Sam being unable to sacrifice his illusion of order. He is tortured by the prospect of not knowing and having to place his trust in a female. In order for him to retain his illusion of order and defend his perceived masculinity, he must force her to strip so that he can know with a certainty that she does not have the bill.

In the end, Sam Spade is a formulaic male chauvinist; a victim of self-inflicted, brutal individuality that hinges upon successfully defending his illusions of order. His inability to cope with supposed threats upon his masculinity estrange him further from society, instead of fortifying his desired place within it. The result is a man bereft of human kindness, and so distracted by the fear of emasculation that he cannot escape his own poisonous illusions. The real damage is done to society and modern masculinity when Sam Spade is viewed as a pinnacle of male achievement. As an icon, Mr. Spade is a powerfully negative image for men to idolize and imitate. His insecurity fueled behavior, if imitated, will create a venomous social climate based on rigid gender roles and perceived masculinity. Although some aspects of his individualism and self-reliance may be applauded, his objectification and emotional abuse of women is horrendous, and such behavior has no claim upon a man’s masculinity.

A central problem with this novel (and possibly the entire noir fiction genre) is that all of the female characters are viewed through a patriarchal, misogynistic lens. Thus they act out the roles that a male author and audience require of them, not necessarily the roles they would actually play. Johanna M. Smith defined it this way: “texts by [Dashiell Hammett] subscribe to a gender-based, individualist ideology in which women are male-defined” (Smith 80). This ideology is dangerous because it reinforces incorrect stereotypes about gender roles and relationships with women. Men can develop unhealthy attitudes and beliefs about women based upon the fictional characters and scenarios portrayed in these revered novels. Much of the social strife and gender paradigm backlash since the 1930s seem to orbit the central issues presented in The Maltese Falcon—it’s because of these themes that the femme fatale archetype is possibly the most recognizable element in the film noir and noir fiction genres (and is continually found in many others). Each story presents another woman to vilify and then defeat, propelling countless misogynistic heroes onto victory. Sadly, The Maltese Falcon is a beloved classic novel that has perpetuated gender conflict for most of the last century.

A parting thought: Stephen Cooper, in his article “Sex/Knowledge/Power in the Detective Genre,” said that “Spade is the genre’s ideological model of male self-containment. [Female figures] function primarily as sexual foils to the detective, [and] also as initial obstacles to and ultimate resources for the detective’s inquisitive/acquisitive will-to-know. Notwithstanding the high profile given to “romantic interests” by the genre, such service suggests the exploitable continuum between, on the one hand, sex and knowledge, and, on the other, knowledge and power” (Cooper 23-24). The point is that all the power in both sex and knowledge rests in Sam Spade. The female characters are expendable victims of his occupation, both detective and male. For in the noir world Mr. Hammett created, Sam must either victimize them or he himself will become the disillusioned victim of robbed masculinity.

By: Chad de Lisle

Works Cited

Abbott, Megan. “”I Can Feel Her” The White Male as Hysteric.” The Street Was Mine: White Masculinity and Urban Space in Hardboiled Fiction and Film Noir. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. N. pag. Print.

Chandler, Raymond. “The Simple Art of Murder An Essay.” The Simple Art of Murder. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1950. N. pag. Print.

Cooper, Stephen. “Sex/Knowledge/Power in the Detective Genre.” Film Quarterly 42.3 (1989): 23-31. Print.

DeFino, Dean. “Killing Owen Taylor: Cinema, Detective Stories, and the Past.” Journal of Narrative Theory 30.3 (2000): 313-31. Print.

DeFino, Dean. “Lead Birds and Falling Beams.” Journal of Modern Literature 27.4 (2004): 73-81. Print.

Entin, Joseph. ““A Terribly Incomplete Thing”: No-No Boy and the Ugly Feelings of Noir.” MELUS: Multi-Ethnic Literature of the U.S. 35.3 (2010): 85-104. Print.

Evans, Verda. “The Mystery as Mind-Stretcher.” The English Journal 61.4 (1972): 495-503. Print.

Hammett, Dashiell. The Maltese Falcon. New York: Vintage, 1992. Print.

Horsley, Lee. Twentieth-century Crime Fiction. Oxford, England: Oxford UP, 2005. Print.

Malmgren, Carl D. “The Crime of the Sign: Dashiell Hammett’s Detective Fiction.” Twentieth Century Literature 45.3 (1999): 371-84. Print.

Paretsky, Sara. “Private Eyes, Public Spheres.” The Women’s Review of Books 6.2 (1988): 12-13. Print.

Porter, Joseph C. “The End of the Trail: The American West of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler.” Western Historical Quarterly 6.4 (1975): 411-24. Print.

Smith, Johanna M. “Hard-Boiled Detective Fiction: Gendering the Ganon.” Pacific Coast Philology 26.1/2 (1991): 78-84. Print.

Walton, Priscilla L. “The Agency of Detectives and the Venue of the Short Story.” Narrative 6.2 (1998): 123-39. Print.

Winks, Robin W. “American Detective Fiction.” American Studies International 19.1 (1980): 3-16. Print.

You must be logged in to post a comment.