Rear Window (1954) directed by Alfred Hitchcock is considered by many critics to be the apex of the suspense genre films. The film stars James Stewart opposite Grace Kelly, with Wendell Corey, Thelma Ritter, and Raymond Burr rounding out the rest of the main cast. With a stellar screenplay from John Michael Hayes (based on a short story by Cornell Woolrich), Rear Window is a touchstone for film quality to this day.

Our protagonist, Jeff, is a world renown photographer who makes his living in the dangerous spaces of the world. One of those dangerous spaces was a race track, where he snapped an incredible picture before nearly becoming roadkill. Now recovering from these injuries in his studio apartment, he finds himself confined to a wheelchair and an itchy cast from hip to ankle. Jeff’s only past time now is spying on his neighbors through broad windows that all face the same courtyard. His socialite girlfriend, Lisa Fremont, is ready to take their relationship to the next level of commitment, but Jeff sees marriage as a prison more permanent than his current circumstance. He escapes her advances through the windows of his neighbors, becoming withdrawn and emotionally unavailable in an attempt to discourage her. Jeff’s nurse Stella, reproves him for being a ‘peeping tom’ but ultimately enables him in the same breath. The plot revolves around Jeff’s seemingly harmless voyeurism gone wrong, when circumstances in a salesman’s apartment across the way lead Jeff to believe that the man has murdered his wife. The sensation of suspense coupled with the anxiety of helplessness collide in Rear Window, from off-handed comments portending trouble to stifled screams in the black of night; the film delivers thrills from opening to closing shot. Although most reviews of the film tend to focus on its incredible treatment of suspense, I assert that this film is birthed from the film noir genre as one of the first true ‘neo-noir.’

Critically, Rear Window is universally praised for its suspense. Roger Ebert relates in his review:

This level of danger and suspense is so far elevated above the cheap thrills of the modern slasher films that “Rear Window,” intended as entertainment in 1954, is now revered as art. Hitchcock long ago explained the difference between surprise and suspense. A bomb under a table goes off, and that’s surprise. When we know the bomb is under the table but not when it will go off, that’s suspense. Modern slasher films depend on danger that leaps unexpectedly out of the shadows. Surprise. And surprise that quickly dissipates, giving us a momentary rush but not satisfaction. “Rear Window” lovingly invests in suspense all through the film, banking it in our memory, so that when the final payoff arrives, the whole film has been the thriller equivalent of foreplay.

His assessment is correct, I believe, because the film doesn’t hide its intentions from the viewer. From the beginning the audience is promised murder, and the suspense is the result of awaiting its arrival; “the bomb” as Hitchcock put it, is under the table and we can hear it ticking. In 1954, Bosley Crowther’s review in the New York Times said that “the purpose of [the film] is sensation, and that it generally provides in the colorfulness of its detail and in the flood of menace towards the end.” That “flood of menace” is what the film does best, and what begins as a trickle of suspense in the end drowns the viewer. Crowther’s compliment concerning the detail present in the film is interesting, because I would argue that it is the conspicuous lack of detail that creates suspense. We cannot see everything that is happening in Thorwald’s apartment, and thus our unease. Reviewer Killian Fox highlights the arguably most suspenseful scene in the film saying, “there is the scene of perfect suspense when Kelly’s character steals into Thorwald’s apartment while he’s momentarily out. Powerless to intercede, Stewart can only look on with mounting anxiety and implore her in a strangled whisper to “Get out of there,” like a jumpy audience member in a horror film, when he knows that the murderer will be returning any second.” The scene she describes is more perfectly suspenseful than any other because the sense of dread is displaced by a degree. Instead of Jeff being the victim in this scene, it is his beloved Lisa Fremont; instead of fearing for his own life at the hands of Thorvald, he fears for the life of the woman he loves. The scene is brilliant because he cannot be brave in the traditional sense; Jeff cannot face his fear with the stiff upper lip of masculinity because it isn’t his own life hanging in the balance. I don’t believe that it is possible to deny Rear Window is a masterful example of suspense.

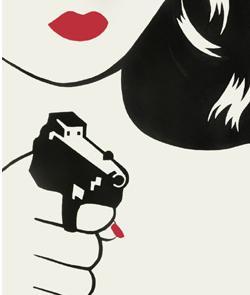

Suspense aside, I believe that Rear Window shares many tropes of the film noir genre out of which it was born. First, the femme fatale is certainly present, though perhaps not in the way you would expect. In traditional film noir, the femme fatale is the woman that brings about the downfall of the protagonist. On her hinges his character’s ability to survive the trials of the plot, and more often than not, she is absolutely central to the development of the action. Lisa Fremont serves this purpose to a great degree in Rear Window. Although she doesn’t necessarily bring about the destruction of the protagonist, her near-death encounter with Thorwald destroys his masculinity. Jeff is reduced to the helplessness of a babe at the sight of Thorwald’s assault; writhing in his chair and whimpering helplessly. He is so unmanned in that moment of suspense that he even lacks the ability to cry out. Additionally, classic uses of dramatic light and shadow are utilized in the film. Tight shots of Jeff’s face half hidden in shadow come to mind, or even the dramatic entrance of Lisa Fremont’s character in the darkness of his apartment serve as examples of textbook film noir tactics. But the most obvious film noir lighting technique would have to be the glowing flare of Thorwald’s cigar in his pitch dark apartment; he glowers over the embers like a fat demon in hell. Finally, I point to the misogyny present in Rear Window. Misogyny is certainly an artifact of the time period, but in the film noir world of gangsters and ‘dames’ it’s inseparable. This misogyny is most clearly revealed when examining the female characters of the film. Miss Torso and the sunbathers are simple outlets of lust for the male creature, their sole purpose to excite the libido. Miss Lonelyhearts entire existence hinges on the lack of affection from men, and she cannot be made whole until she finally receives it. The newlyweds are wholly confined to the marriage bed, and what begins as the exciting expression of a sacred union becomes the begrudging obligation of an ‘abused’ husband. And finally Lisa Fremont herself, a supposedly influential and independent woman, is reduced to yet another female character stuck in the orbit of the male protagonist. All of her growth throughout the film serves to impress upon Jeff that she would be a good wife afterall. Each of these examples serves to reinforce the idea that Rear Window is created from and continues the film noir tradition as a form of ‘neo-noir.’

Ultimately, I praise this film for its achievement not only as a wonderfully visual and suspenseful journey, but also as a work of adaptation. I can see Cornell Woolrich adapting it from the noir crime/film noir genre of stories, and John Michael Hayes adapting it from Woolrich, and then finally Alfred Hitchcock adapting it from Hayes with each layer of adaptation polishing the story just a bit further than the last. This collective creative effort is why I believe that Rear Window may straddle genres and still incite wonderful scholarship from its release to our present day.

Reviews Cited

You must be logged in to post a comment.