“Do you love her?” Gene whispered.

“No,” Jack said. “No, I guess I hate her.”

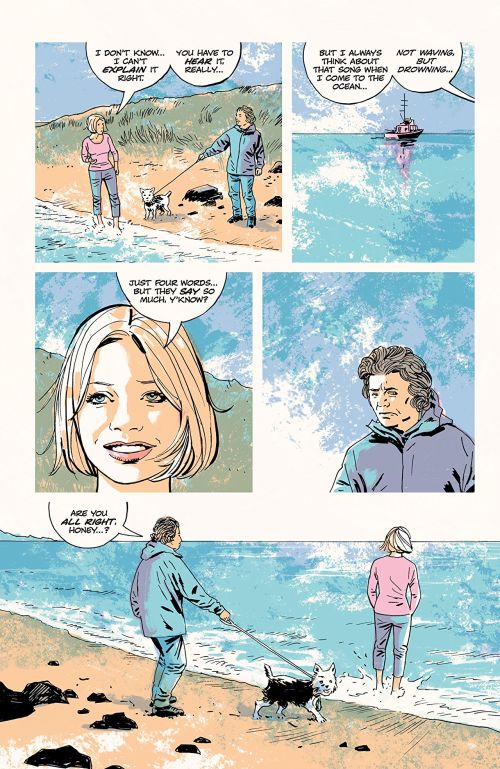

I’m fascinated by destruction. Enthralled. I crane my neck as I pass the smoking ruin of a car on the highway; I peer past the flashing lights hoping to glimpse the nucleus of the disaster. What happened? Give me the gruesome details. Don’t sugarcoat it. Most are like me. Whipping around the periphery we’re held in orbit by forces we can’t explain. How can we not know? When the knowledge of a tragedy migrates from the recesses of our mind, rolls rough past the lump in our throat, and punctures the flowing curtains of our heart, the tears well unbidden and remind us of our humanity, our fragility. Tragedy in others stirs gratitude in ourselves. We’re grateful we weren’t chosen…this time.

So Many Doors by Oakley Hall is a tragedy. The accompanying catharsis of the novel is a welcome guest, like greeting a friend after a long bout of loneliness. For me, it was less a work of noir crime fiction than it was a romance novel, minus all the beauty and eroticism; an ode to human suffering on behalf of love, lust, & ego. Life & death permeate the pages. The touchstone of a great novel is its ability to convey something true of the human experience, and Mr. Hall’s work meets the criterion.

Is all noir tragic in nature? I’ve oft written of the inevitability of the noir plot: the way the protagonist careens toward painful endings as if drawn by pitiless gravity. So frequently is the hero punished we cease blaming fortune and instead call it fate. “He was meant to suffer.” (Perhaps it’s easier to explain our own daily suffering by assigning it meaning?)

Oakley Hall

The novel revolves around two lovers, Jack & V. They’re no good for each other.

“He’s got that something women like,” she said. “Those eyes and those big shoulders and those little-bitty hips, and when he looks at you sometimes you know you ought to slap him but you don’t really want to.”

The Anti-Hero

Jack is a beautiful man-piece. A hard-working, good looking, road working man known as a “cat-skinner” – he has everything going for him. His confidence is astounding. Other men simultaneously admire him and hate him. He’s a ladykiller. The only problem is, he’s killed the wrong lady. He first meets V while removing stumps on her daddy’s farm one summer. She’s a teenager. She’s naive. She’s easily won. What could have been, and should have been, a beautiful relationship is cheapened by his selfish behavior and lack of commitment. He uses her. He takes her virginity, gets her kicked out of her home, and eventually dumps her. Only, she won’t leave him alone, not after she discovers that she has all the tools to win him back and the wherewithal to use them.

As she passed him he saw her face. It shocked him. It was as though it had been, for a moment, agonizingly contorted into the shape of everything inside her. But there was no grief there now, no fear; there were only the hard, cold angular lines of complete determination. It was as though every quality but this had been suddenly wrenched out of her; as though all there was left was an iron and single-minded resolution. Revenge, he thought, and with the glimpse of her face, the thought frightened him; but then he knew it was not revenge. Knowing what it was he felt tired and wrung, and all at once the feeling welled up in him that he had to get away from this. He was going to get away from this.

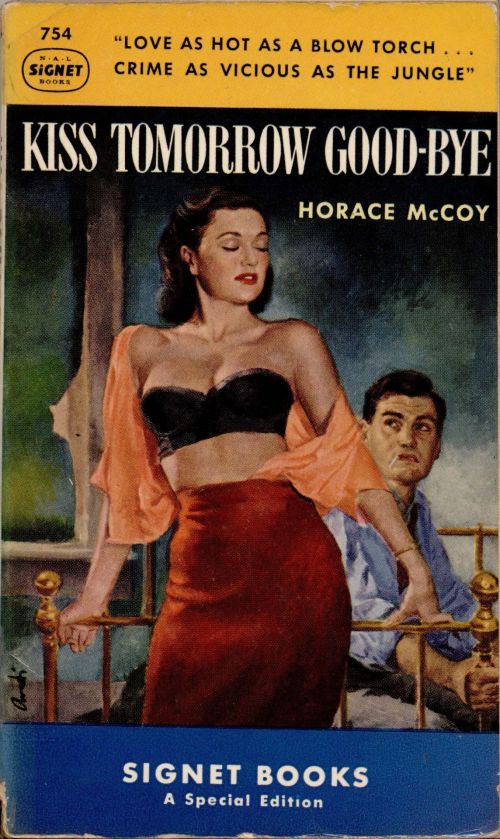

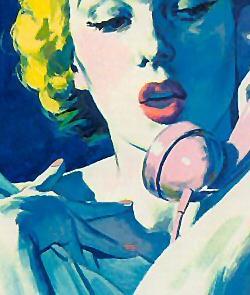

The Femme Fatale

V is a dime. A vivacious cowgirl budding into glorious womanhood. She’s curious, rambunctious, and loyal to a fault. She falls hard for Jack, and almost loses herself in the falling. But at rock-bottom, she’s greeted by an epiphany: Jealousy can be a weapon as real as any blade, a bond as real as any rope. V becomes a peddler of jealousy. Half-desperate, half-crazy, Jack loses himself in her pursuit only to find that the lovely rose of their love is now only a stem of thorns. Only one conclusion is possible, and it’s punctuated by a gunshot.

She’d had the tools. He’d told her she had the tools, if she only knew how to use them. He said, half to himself, “I didn’t know you’d learn to use them this well…You didn’t know when to quit hitting him.”

Oakley Hall is a magnificent author. So Many Doors is a wonderful book. Read it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.